Look what we’ve got for you!

Promoting library collections

Summary

Librarians put a lot of time and thought into the question “what to buy for the library?” to meet users’ needs as best as possible. But what happens once a book or a database or a journal has made it onto the (virtual) shelf? How do users learn about new acquisitions or other interesting holdings? In this article, we take a tour through collection-marketing activities by academic libraries, highlighting some interesting examples and collecting ideas for reuse.

Method: We scouted the internet presence of all IATUL member libraries, considering their websites and, if available, their web 2.0 / social media activities. We added findings from literature and from chance encounters.

Results: Our data collection provides an overview of collection-marketing activities in academic libraries all over the world. We discuss the different types of activities, present some examples that we consider interesting, and share insights into recent activities at one of the authors’ libraries.

Limitations: We can only analyse the activities of those libraries that use a working language we understand, which rules out some libraries that don’t have, e.g., a version of their website in English, German, French, or a Scandinavian language. Moreover, we only consider the perspective and activities of the libraries – but not the perspective and expectations of their users. Investigating whether they have informational needs about collections that are not yet met by libraries would be an interesting complement to our study

Zusammenfassung

Bibliothekar*innen verbringen viel Zeit damit, sich zu überlegen, welche Medien sie für ihre Bibliothek kaufen sollten, um den Bedürfnissen ihrer Nutzer*innen am besten zu entsprechen. Was aber passiert eigentlich, nachdem es ein Buch oder eine Datenbank ins (virtuelle) Regal geschafft hat? Wie erfahren die Nutzer*innen von Neuerwerbungen oder anderen interessanten Beständen? Dieser Artikel sammelt ausgewählte Bestandsbewerbungsaktivitäten verschiedener wissenschaftlicher Bibliotheken, die sich zur Nachnutzung eignen könnten.

Vorgehen: Wir werten die Websites und, so vorhanden, die Web-2.0- bzw. Social-Media-Aktivitäten der Bibliotheken aus, die Mitglied in der IATUL sind. Dazu kommen Literatur- und Zufallsfunde.

Ergebnisse: Unsere Sammlung gibt einen Überblick über Verfahren zur Bestandsbewerbung in wissenschaftlichen Bibliotheken aus aller Welt, die wir anhand von Beispielen vorstellen, ergänzt um einen Bericht über einige jüngere Maßnahmen in der Bibliothek einer der Autor*innen.

Einschränkungen: Wir können nur die Aktivitäten derjenigen Bibliotheken auswerten, deren Website in Englisch, Deutsch, Französisch oder einer skandinavischen Sprache verfügbar ist. Außerdem nehmen wir nur die Perspektive der Bibliotheken ein – nicht aber die ihrer Nutzer*innen. Eine Analyse, die der Frage nachgeht, welche Erwartungen und welchen Informationsbedarf sie rund um Bibliotheksbestände haben, denen die Bibliotheken bislang noch nicht entsprechen können, wäre eine interessante Ergänzung zu unserer Studie.

Voß, Viola: GND 129295612, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3056-407X

Hamrin, Göran: ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4256-2960

1. “Buy and hide” or “Show and tell”?

“Here’s a new edition of a widely used textbook on linguistics. Also available is this package of 25 new sociology ebooks. We decided to licence this new journal about international law. And these three new books will hopefully be interesting for our biologists!” Librarians all over the world probably think like this when going through lists of new titles, new ebook packages, course reading lists, book reviews, and other sources for publications. They not only spend a lot of money, but also a lot of time choosing media for their collections.

But once decisions about acquisitions or licences have been made, sometimes perhaps after long considerations about how to spend limited budgets to best meet the users’ needs, and once the new resources have made it onto the (virtual) library shelves, that’s about it in many cases: Many librarians hope that the new books or journals or databases will be found and read or used, while sometimes not doing much to promote them – and then they are sad when they discover that many of the nice and interesting media they bought are rarely or even never borrowed, downloaded or used, classified as “Dead on Arrival” (DOA)1 in the worst case.

“Why bother?”, one could ask, claiming that students and faculty will come across the resources they need – and if not, they do not need them. But as users have neither the time nor the possibilities to monitor new publications the way librarians do, making it easier for them to keep up with new literature and to make interesting, unexpected discoveries (hashtag serendipity) can be a helpful service.

There are some well-known “classics” of collection marketing, such as new acquisitions shelves in a library and new acquisitions lists on the library’s website for freshly arrived media, or exhibitions or reading lists with books on a certain topic for existing collections.2 But what if the shelves can only be seen by a small number of library users coming into the building and passing by? How do you put ebooks on a “real-life shelf”? What if it turns out that faculty have never heard of your online lists? And alongside these questions, a new one arises: Are there other ideas out there? The authors of this article wanted to know, and so they set off on a little virtual expedition: How do other libraries promote their collections? That is … if they do.3

This “hunt for ideas” concentrated on ways of marketing new acquisitions, i.e., resources recently bought or licenced by libraries for their users. Marketing other media like open access publications or new documents on the library’s document repository would also be interesting topics, but ones for a different project.4 The survey of a set of library websites and a look into the literature resulted in a little “pool of ideas” that libraries can use for inspiration.

The findings will not be assessed according to their effectiveness or their best practice suitability, though, as this is difficult to judge from the outside and may differ for each library. The use of a physical book, e.g., can be measured in the “number of borrowings”, but that covers only part of its usage: When users read it or copy or scan parts of it inside the library building without checking it out, this usually can’t be tracked. For ebooks, “click numbers” can be quite detailed if the platform they are published on offers figures for “downloads of the complete book”, “downloads of single chapters”, or “duration of online reading”. However, once a book or parts of it are downloaded, their offline usage can’t be pursued further. Apart from the availability of detailed usage data, one also has to take into account criteria against which the mere numbers have to be put in perspective: the size of existent collections, the budget available for new acquisitions, the size of the potential “audience” within the university or research group the library is primarily serving, the current trends in their teaching and research, and so on.

This article has its origin in one of its authors’ reflections on how to let students, graduates, and faculty of her disciplines and subjects know about new media purchased for her library. The second part of the paper will therefore take a closer look at some of the activities that were started at her library, partly inspired by findings of the survey presented in the first part of the paper. Here some statistical data can be given. Nevertheless, the main interest of this article remains in compiling ideas for collection marketing, not in providing detailed success statistics or recommendations about what to adapt.

2. Promoting library collections all over the world

2.1. Data collection

We followed two trails for finding examples for collection-marketing activities: On the one hand, we analysed the websites of the IATUL member libraries5, and, on the other hand, we scouted literature, random findings, and recommendations by colleagues. We went through the websites looking for any links or information regarding new acquisitions or featured collections. We did not contact the libraries, merely surveying their websites. The survey was finished on June 7th 2021.

We did not define a concise set of criteria for assessing the type of information in question, as it can be available (or not) in different areas on occasionally quite complex websites and be given in a variety of ways. We also did not want to limit our scope in advance but chose instead to be open for all that we might find. Furthermore, as the main idea of this project was a broad collection of findings and not a detailed analysis of, e.g., the exact position of given information in a website and their number of occurrences, a detailed checklist or a standardised protocol, similar to user-interface studies or link harvesting by web crawlers, was not put together.

In cases where the libraries of a specific university faculty or institute are registered as a IATUL member, we also took into account the website of the “parent” university library.6 For presenting subject-specific information, many Anglo-American libraries use the LibGuides system7 while others publish it within the “normal” library website. We generally refer to these kinds of subject, topic, or course specific areas of library websites as LibGuides, independent of technical implementation. In some cases, we could not analyse a website: Some sites were unreachable, some sites were only available in languages the two authors don’t speak, i.e., languages other than English, German, French, or Scandinavian languages. It could, of course, be that we overlooked information that might be “hidden” on deep websites and hence classified that website erroneously as “giving no information”. But if two experienced librarians cannot find a certain type of information on a library website, even after having reviewed these cases twice, a “normal user” of that library might also not find it – and that website is probably not a suitable example for a collection of good practices.

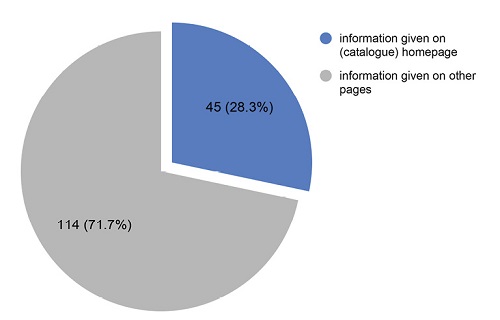

We went through the websites of 243 libraries. 13 sites, or about 5 %, could not be assessed: 2 did not work during multiple access attempts, 11 were only available in languages the authors do not have sufficient knowledge of. Of the 230 sites that could be assessed, 159, or about 69 %, offer some information about new additions or other elements of the collections, while 71, or 31 %, do not give this kind of information. Of the 159 libraries that do, 35 invite their users from the homepage to have a look at their new acquisitions, offering a link to acquisitions lists or presenting them in a box or a cover image slider. 11 do so on the start page of their catalogue or discovery system; one library does both. The other libraries mention information about new or noteworthy media in places like subpages about their collections or in LibGuides, the latter being a typical spot to put this kind of information: Subject guides can link to subject-specific new acquisitions lists and they can recommend books or databases of special interest. We even found 6 guides especially for new acquisitions.

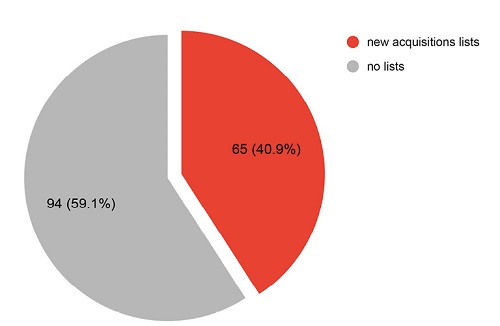

New acquisitions lists can be found in 65 libraries. 37 of these lists seem to be generated automatically, for example via a search in the library’s catalogue or discovery system filtered by date of addition to the collection. 21 are presented in PDF files, which sometimes are out of date by several months. 11 libraries mention new or recommended media in blog posts, and 9 use social media like Facebook and Twitter. Most of the posts are relatively sporadic.

There are some aspects that could be explored in more detail in similar analyses: For the dichotomy of promoting only new or also older collection items, we have seen a, probably natural, tendency to prefer highlighting new material, but we have not recorded exact figures on this. “Promoting older items” may overlap with “promoting special collections”, so this could also be an aspect worth looking out for, as is the question of which type of media is being promoted, e.g., printed books, electronic books, databases, or database trials. From a technical point of view, it might also be interesting to analyse whether the information about new or interesting collections is made available only as “static” information as in “presented on the library website” or also as “subscribable information” as in “interested users can subscribe to an RSS feed or an email alerting service”.

The numbers presented here are only intended to give a rough overview of the websites we have visited; we will not make further use of them in the following, as a detailed statistical evaluation is not the focus of this article.

2.2. Findings and examples

In this section, we present some of the activities displayed by IATUL libraries we assessed as good practices; in case we had special observations we will mention them accordingly.

2.2.1. New acquisitions lists

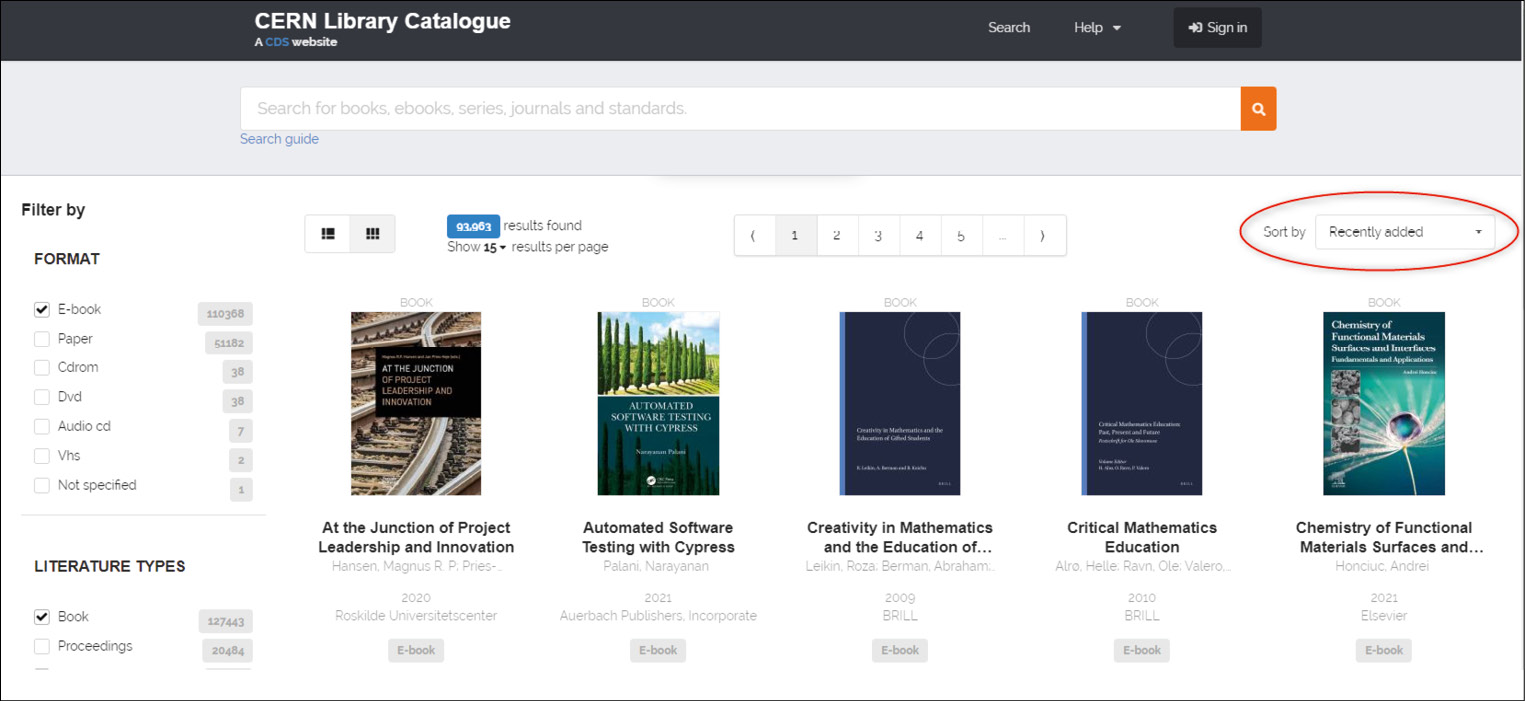

We assume that today nobody wants to – or has the time to – manually put together lists of new media acquired for a library. While obviously “manual” solutions are still around, there are now more up-to-date solutions like lists generated and published on a monthly or weekly basis or “living” lists generated via queries in the catalogue or discovery system filtered down to the newest additions. An example for this can be found at the CERN Library8 in Switzerland (see fig. 3).

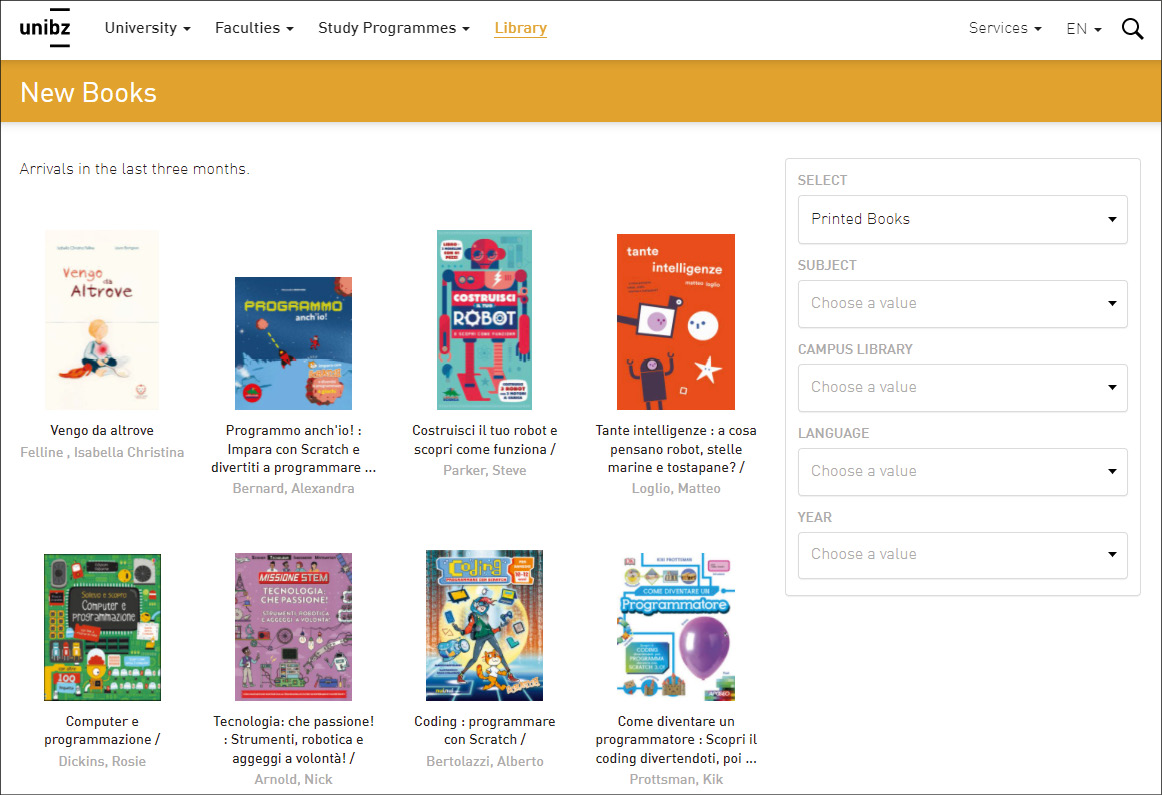

As physicists are probably usually not that interested in books about French grammar and Romance Studies scholars won’t often be looking for publications about quantum physics, it might be a good idea to offer subject-specific lists, as do, e.g., the Tshwane University of Technology Library9 in South Africa or the University of Konstanz Library10 in Germany. The Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Tirol at Innsbruck University, Austria, offers a choice between “new books by subject” or “new books by library”11. At the library of the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano12, Italy, you can also filter the list of new printed books or ebooks that arrived in the last three months for the faculty library they are located in (for printed books), the language, or the publication year (see fig. 4).

Ideally, these lists can then be subscribed to via RSS or an email alerting service, like at Massey University Library13, New Zealand (see fig. 5), or Sabancı University Library14, Turkey.

Some libraries offer different lists for printed and electronic books. We think this might be an outdated approach: The physicist or the Romance Studies scholar would have to scout two lists instead of one – so better include both media types on one list.

At the other end of the line, it is also an interesting idea to inform users about resources that libraries have to part with, like journal or database cancellations. Examples for this can be found at the “2020 Arrivals and departures” page of the University of Adelaide Library15 in Australia or at MacEwan University Library16 in Edmonton, Canada. These websites may offer an opportunity to give some background information on why there were cancellations and how they were decided on, thus making not only acquisition, but also deacquisition decisions more transparent for library users.

2.2.2. Positioning the information on the library website

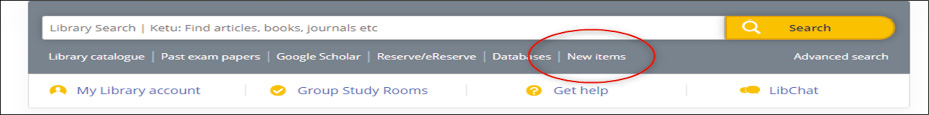

While it is quite “inviting” to point users to information about newly acquired resources directly from the homepage of a library website, space is limited, and many services are competing for a spot here. Some libraries have found a good solution for this, nevertheless, like the University of Otago Library17, New Zealand, with its small “New items” link under the search box (see fig. 6), or the library of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology18 with a tile for “New Arrivals” in a slider for news and services.

Boxes with cover images, perhaps presented in a slideshow or a carousel, may be a good way to present the service while also “livening up” the homepage or special pages for new acquisitions graphically, like on the homepages of the library of the Università Bocconi19, Milano, Italy, or the library of the Islamic University of Technology20 in Gazipur, Bangladesh (see fig. 7).

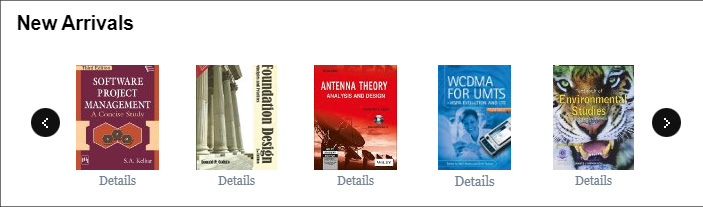

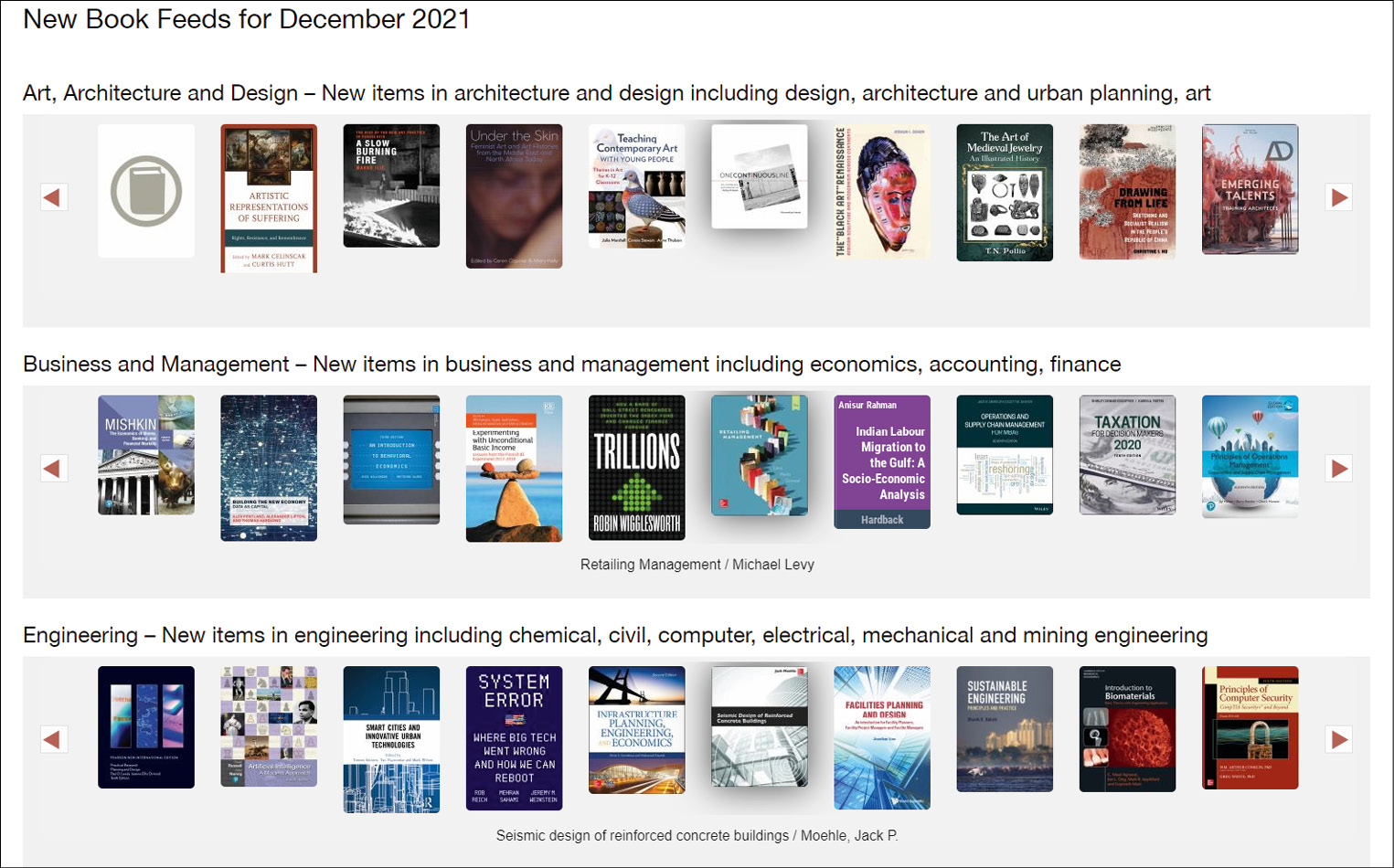

On “new books” pages, book covers presented in carousels or virtual bookshelves can give a nice “look and feel”, as seen at Curtin University Library21, Australia, where you can even choose between different visualisations. Another example is the page for new books of the American University of Sharjah University Library22, United Arab Emirates, where you can browse different subject-specific sliders (see fig. 8).

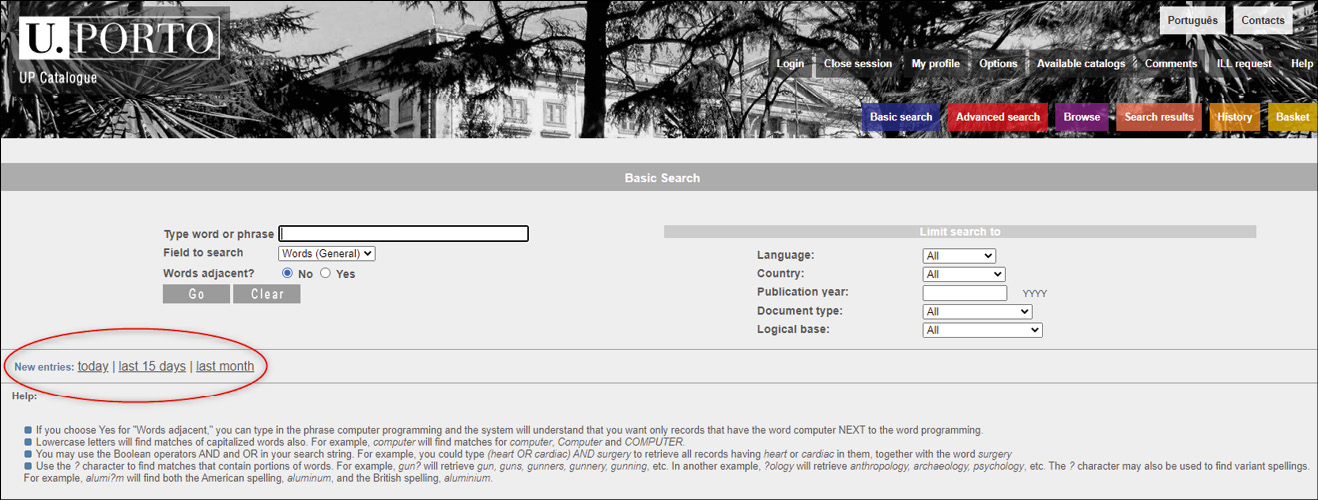

Another good place to find out more about new media may be the homepage of the catalogue: As many users bookmark the catalogue for quick reference, they might visit it more often than the library homepage. Examples can be seen at the library of the Technical University of Chemnitz23, Germany, with a link to “Recent Acquisitions”, at the University of Porto library24, Portugal, with three different lists for “New entries” (“today”, “last 15 days”, and “last month”) (see fig. 9), or at the Beirut Arab University Library25 with “New arrivals” sliders.

Other “logical” spots for linking to this kind of information are the “collections” and the “tips for your literature search” areas of the library’s website, like at Macquarie University Library26, Australia, or at Hildesheim University Library27, Germany.

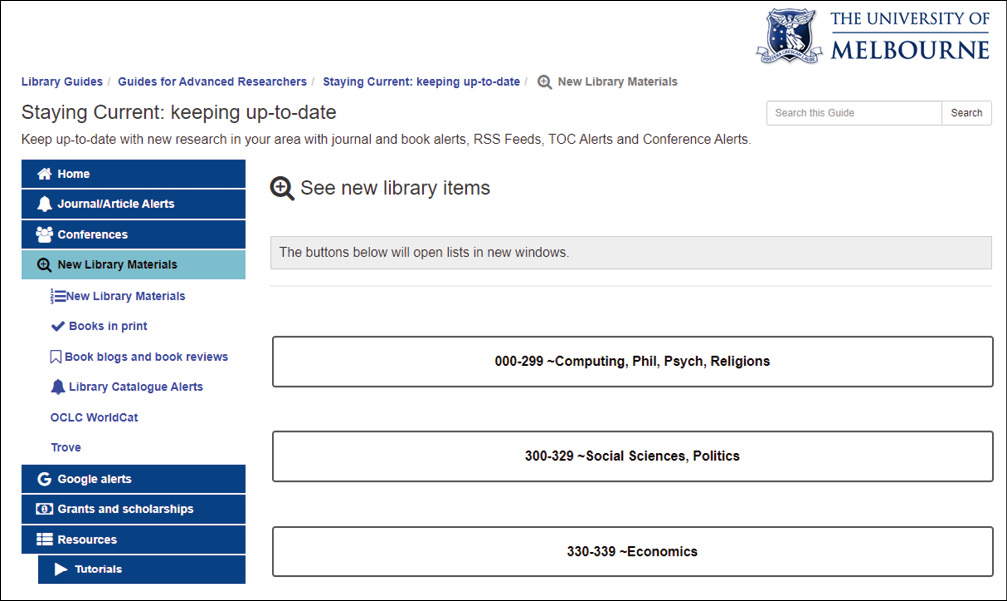

Under the label “Current awareness services” it also fits in well on sites about services for researchers, such as on the “Current Awareness” page of Beirut Arab University Library28 or in the LibGuide “Staying Current: keeping up-to-date” of the University of Melbourne library29, Australia (see fig. 10).

If the library wants to inform students or researchers on a subject-specific level, an obvious place would be LibGuides and similar websites. Subject librarians can recommend single media, generate lists of new acquisitions for the subject in question, or promote new databases or databases currently on trial. The library of the University of Turku, Finnland, does this, e.g., in the “Education” LibGuide30. The Kadriye Zaim Library at Atilim University in Ankara, Turkey, runs a “Books & eBooks” LibGuide for Engineering31.

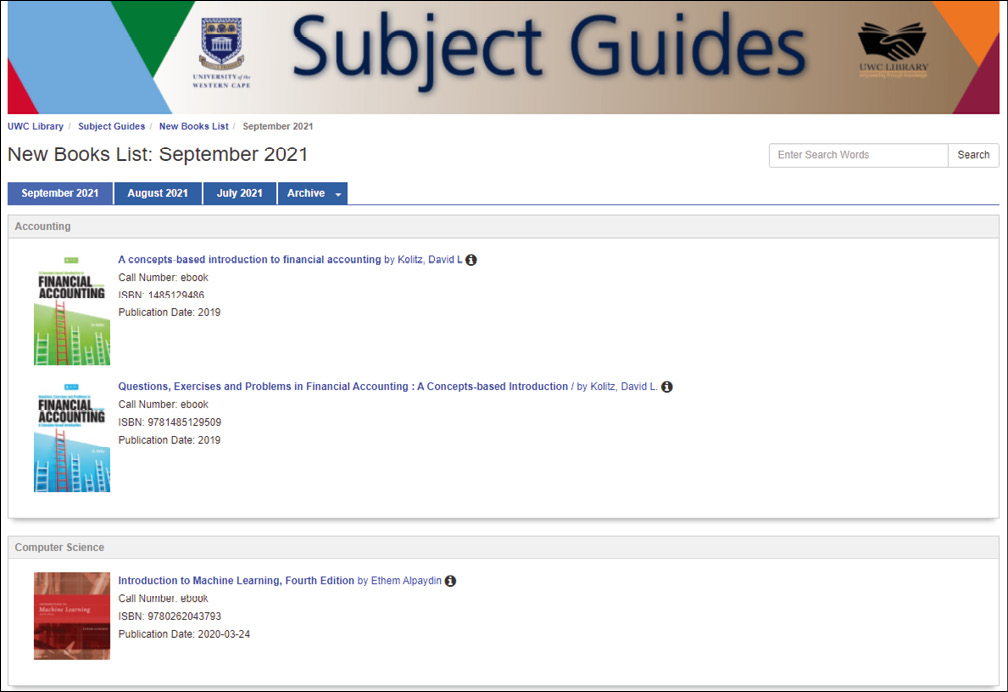

An interesting alternative are special LibGuides for new resources and database trials, like the “New Books List” Guide of the University of Western Cape in South Africa32 (see fig. 11) or the “Trial databases and new electronic resources” guide of Deakin University Library in Australia33. Here, this kind of information can be “herded” in one place which is often easier to edit than normal websites.

There might be a danger of these LibGuides getting lost in a multitude of LibGuides, though: If a library runs dozens of guides, it should make sure there are ways of sorting or filtering the guide lists, like in Melbourne34.

There are many more ways to place links to new acquisition and similar information on a library website. Some of these places are well hidden, making it rather unlikely that users will find them. It also feels a bit strange that information about inter-library loans is much more prominent on many websites than information about local collections!

2.2.3. Using social media and other tools for collection marketing

Social media are a good way of communicating all sorts of information to different types of library users: Content can be published more easily than via a complex website content management system, and it may more effectively reach the audience than via the library website.

Some libraries have established long-running series for marketing collections like “Maud’s e-Resource of the Week” by McMaster University Library35 in Hamilton, Ontario, USA (Maud being the library’s mascot eagle), or the “Book of the week” series by the library of the Indian Institute of Technology36 in Gandhinagar, Gujarat.

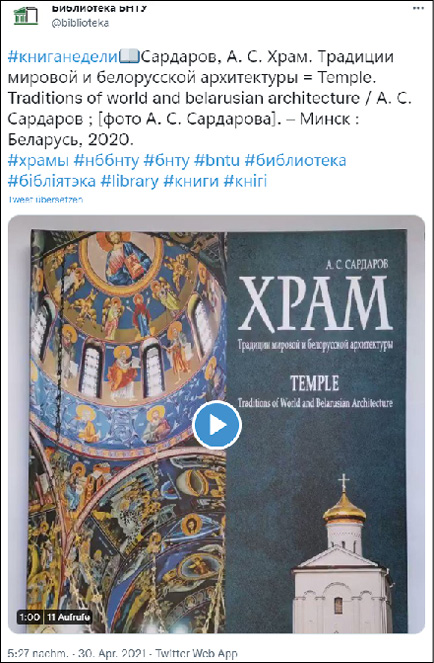

With smartphones at hand, the library team can easily share new insights like leafing through a new book, as the Belarusian National Technical University Library in Minsk does in little videos accompanying their new book tweets (see fig. 12).37

The library of Kingdom University Bahrain runs a WhatsApp group about new resources (see fig. 13)38 – an approach easily accessible to the user but questionable from a data privacy perspective.

2.2.4. Findings at non-IATUL libraries

Looking for LIS literature about collection marketing, we found that there are publications about topics as diverse as “how to allocate budgets for the different subjects within a library”, “how to choose items for the library”, “how to prevent them from being stolen”, “how to track them via RFID”, or, in the end, “how to weed your collections” – but promoting new acquisitions or older collections, especially in academic libraries, is not often dealt with. Despite that, we collected some interesting examples for such marketing activities, supplementing the findings from literature with others we encountered by chance or through recommendations from colleagues. Examples are given alphabetically by location of the libraries (town/city name).

New acquisitions

|

Fayette, MO, USA |

Central Methodist University › Smiley Memorial Library |

Pinterest boards for new books, new DVDs, |

|

Göttingen, Germany |

State and University Library |

New acquisitions lists inLibGuides, individualised lists possible via choice of subject areas, RSS feeds per subject available40 |

|

Groningen, |

University Library |

Hashtag #Cybermonday to promote new ebooks41 |

|

Hagen, Germany |

University Library |

New acquisitions lists sorted by subject |

|

Hamburg, Germany |

DESY43 Central Library |

“New items in library collection” list giving classification and shelf marks “in shelf mark label optics” for easy recognition44 |

|

Leuven, Belgium |

KU Leuven libraries › Artes University Library |

“New acquisitions in the picture” box on the start page linking to the new acquisitions list and new acquisitions list sorted by library location and subjects45 |

|

Munich, Germany |

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek › Specialised Information Service for Russian, East and Southeast European Studies |

Presentation of selected new acquisitions on Twitter with the hashtag #kOSTprobe46 |

|

Münster, Germany |

A library user on behalf of Bücherei an der Mauritzkirche (Parish Library of St. Mauritz Münster) |

Using the neighbourhood platform nebenan.de for advertising new acquisitions47 |

Older collections

|

Berkeley, CA, USA |

University of California › |

Box “Summer reading” tips in carousel box on start page, directing to the corresponding category in the library’s blog48 |

|

Charleston, IL, USA |

Eastern Illinois University › Booth Library |

“RefNews” blog created 2016 to “showcase specific resources in [the] collections (physical and electronic and often both) that might otherwise go unnoticed”, scheduled tweets, and Facebook posts for the blog posts49 |

|

Evansville, IN, USA |

University of Southern Indiana Library |

Twitter hashtag #BooksYouDidntKnowWeHad for promoting diverse collections50 |

|

Hannover, Germany |

University of Applied Sciences |

“Journal of the month” blog post series51 |

|

London, UK |

Brunel University Library |

“Book stop displays”: exhibitions of materials grouped “together under themes relevant to the life of the university, responding to the collections or to what is going on in the wider world”, each display accompanied by a blog post and a Pinterest board “Pop-up libraries” on campus, using an iPad for mobile check-out52 |

|

Tübingen, Germany |

University Library |

“Books To Go”: monthly thematic collections of books in a shelf for direct borrowing plus blog post plus online reading list53 |

|

Vienna Austria |

University Library › Jewish Studies Library |

“Ebooks of the month” list54 |

|

Zürich, Switzerland |

Zentralbibliothek Zürich (hashtag used also by other libraries55) |

Hashtag “Datenbankdienstag” (in English “database Tuesday”) for promoting databases56 |

Other activities

|

Durham, UK |

Durham Residential Research Library |

Research fellowships from one to three months designed “to increase use and knowledge of collections”57 |

|

Houston, TX, USA |

University of Houston |

Development of an “Image Café” for |

|

Lubbock, TX, USA |

Texas Tech University Libraries |

Development of a set of marketing activities for their digitised special collections focusing on community connection, including an honest review of their first – not very successful – campaign59 |

|

South Orange, NJ, USA |

Seton Hall University › Valente Italian Library |

Visual representations of the library collection60. Perhaps new acquisitions could also be presented in such a visual way? |

|

Tuscaloosa, AL USA |

University of Alabama Library |

Development of a collection-marketing program consisting of digital sign images, a carousel on the library homepage, and |

|

General |

Applicable to all academic libraries |

Sending an email mid-term “updating the faculty liaison about the funds left to spend, if applicable”, attaching “a list of purchases since the beginning of the fiscal year”, and sending another email at the end of the semester thanking “the faculty liaison and the department for their participation during the fiscal year, and send[ing] a list of all resources purchased during the year”62 |

|

General |

Applicable to all libraries |

If a library wants to use Twitter for advertising resources but does not have a RSS feed source for that, “autochirp”, a tool for scheduled tweets based on a spreadsheet, might be an idea63 |

2.3. Where to go from here?

The examples presented here hopefully give a good overview of activities for promoting new acquisitions of academic libraries around the world. Although there is extensive literature on library marketing, as far as the authors can tell, there has not yet been any similar broad survey. As mentioned in the introductory chapter, we do not intend to provide a detailed discussion of these examples here: Relating the findings to the theory of library marketing, evaluating them for their implementation costs and their assumed effects, or developing ideas about how to weave interesting activities into the marketing strategy of a specific library remains the task of future publications. Starting points for this may be found in the relevant literature.64

As one example for how a practical implementation of new activities can look like, we round off our collection of examples with a closer look at a German library.

3. Picking out one example: Recent activities at Münster University Library

3.1. The situation in 2018

When the first idea for this paper came up in late 2018, Münster University Library (MSUL) was providing information about new acquisitions or special collections through four channels:

- Weekly new acquisitions lists65 based on subject markers new books get during acquisition;

- New acquisitions shelves in some of the faculty libraries;

- Announcements of new databases in the central library’s news feed66;

- Temporary references to new acquisitions on the LibGuides-like pages for linguistics and literature studies67 on the library’s website (two acquisitions per month, chosen subjectively on criteria like “current trends”, “interdisciplinary approaches”, or “interesting special interests”).

So, this was a typical “web 1.0” situation, probably representative for many other (not only German) libraries. Information could be delivered, but the channels had and still have several downsides:

- Users could subscribe to being notified about new issues of the new acquisitions lists only by subscribing to the library newsletter (sent out on an approximately monthly rhythm) or to the general news RSS feed. But there was no single feed dedicated to acquisitions, let alone a feed for only one subject. There was no email alerting service for these lists (which might be of interest as not many students and faculty use RSS feeds, as far as we know). These factors might contribute to the fact that many library users are not aware of these lists.

- “Analogue” new-books shelves in libraries could be interesting for regular users of these libraries but were less useful for most other users.

- The central news channel was filled by the libraryʼs online editorial team, leaving the subject librarians having to ask the online team to publish subject-specific news. The channel also did not offer a comment function.

- The reference to new media on the LibGuide pages had to be taken down after a while to prevent the pages from getting overloaded, which was at times frustrating and caused double work. There was no way for users to subscribe to these and other news items, e.g., about interesting websites published on these pages. And the publication of the next month’s news had to be done “just in time”, as the web content management system did not allow for scheduling of page edits.

3.2. The new set-up since 2019

Becoming more and more dissatisfied with this situation, one of the authors of this paper, subject and liaison librarian for the Humanities at MSUL, thought about whether web 2.0 tools might help. A first idea could be found close by: For several years, the Medical Library of MSUL had been using a weblog for library news,68 making it easier for more staff members to post news. Other libraries had also started using blogs for general or special news, and more and more libraries had begun using social media like Twitter as an additional information channel.

The technical set-up of the MSUL website and news feed was not going to change in the near future. Thus, new tools and channels had to be planned as additions to the existing systems. This meant that while they had to be asked for as a sensible combination or integration, it also offered some freedom as no changes to the existing systems had to be done. In January 2019, a weblog for the subject and liaison services at MSUL was launched (see fig. 14).69

Based on an easy-to-use WordPress system, it offers all subject librarians the possibility to publish posts regarding their subjects without having to ask the online editorial team. The posts can be scheduled and thus prepared in advance. They are categorised and tagged according to the subject(s) the information is relevant for and formal criteria like “new acquisitions”, “from our collections”, “link tips”, etc. Readers can subscribe via RSS feed to the entire blog or to single categories or tags, and they can leave comments. As blog posts are indexed by search engines, they can also be found via search engines, helping to make the featured collections even more visible.

The RSS feeds can also be used to deliver blog posts to other websites: In the author’s LibGuide-like pages, there is a “news” page for each subject fed with posts from the MSUL Subject Services blog and other interesting sources (see fig. 15).70 The feeds are set up once, then the page is kept up-to-date automatically. Via RSS feeds, another channel can be filled: The MSUL Subject Services Twitter account71 that was set up in January 2020 automatically tweets links to new posts via the service IFTTT (see fig. 16).72 The Twitter account is also used to promote more new acquisitions that might have been “triggered”, e.g., by reviews found on other Twitter accounts, to point out events at Münster University, or to give link tips for teaching and research.73

Writing blog posts for the eight subjects the author is in charge of76 takes about 45 to 60 minutes per month per subject, so about 8 hours per month. For each subject, there is one post per week, public holidays excluded. Tweets are written or retweeted “on the fly” if an occasion occurs, e.g., when the author goes through her Twitter timeline. The time required for these two channels is therefore within manageable limits. As blog posts can be scheduled, their writing can be fitted freely into the to-do list. Writing them is not tied to a specific day or date. In contrast to the previous process, blog posts are available permanently, and individual posts can be referred to via email or Twitter.

What’s more, the current set-up – blog, Twitter, RSS, IFTTT – allows for an important prerequisite the author had in mind: Write a post once, use it in several different settings without any further “expense”.

3.3. Are there measurable effects? Looking at printed books loans

As mentioned briefly in the introductory chapter, effects of marketing activities are not easy to measure, and the aim of this paper is to collect ideas, not to sort them by effectiveness. But for MSLU, there is one aspect that can be evaluated statistically: In the first week of every month, there are blog posts promoting two new acquisitions per subject.77 Hicks, White, and Behary78 have found positive correlations between the promotion of new titles in their library’s LibGuides and the borrowing or download numbers of these books.

Curious to see whether a similar correlation can be found at MSUL, we took a look at the numbers for the books promoted in the blog. Between January 2019 and June 2021, 420 books were recommended. Since one title was posted twice, we can include 419 books in our calculations. At MSUL, 309 of these books are print editions, 86 books are ebooks, and 24 books are available in both formats. The usage data available for the ebooks had no sufficient coverage, so we limited our analysis to the 333 printed books. We compared the number of loans in 2020 with the statistics of a) all other books in the MSUL collection published between 2018 and 2021 and b) the subset of all books allocated to the eight subjects and published in the same period. Between the books mentioned in the weblog and all other 2018 to 2021 books, there is no significant difference in the distribution of the loans statistics, but between the books mentioned in the blog and the other books for the same subjects there is: The featured books have been borrowed more often than the books not featured. We conducted a χ²-test of homogeneity to compare the distributions.79 In addition to other possibly relevant factors like “books mentioned on course reading lists” or “people who happen to be working on the same topics”, we attribute part of this result to the blog posts.

3.4. Future steps

The current set-up works well and will be continued for the time being. Repeating the usage analysis of the titles featured in the blog in a few years might be interesting to track development of the data, as “[r]esults do not come overnight”80 – an insight that applies to marketing activities of all kinds.

In March 2021 a new blog category81 was added: Inspired by an idea mentioned in Armstrong/Dinkle (2020)82 and by a question in a long-running interview series in the German weekly newspaper “Die Zeit”, faculty of Münster University recommend books (or articles) they consider fundamental for their teaching or research, inspiring for their own career path, or otherwise relevant to them. It might be interesting to see whether there will be a correlation with the usage of these titles as well.

MSUL will introduce a new library management system and a new discovery system in August 2022.83 It remains to be seen what new possibilities this may open up, for example for new acquisition lists sorted by subjects that are easier to subscribe to. Besides that, we will think about ways to inform our students and faculty about interesting new open access literature or about titles in big ebook packages or from Evidence Based Acquisition or Patron Driven Acquisition projects. Going through the activities of other libraries, as done in the first part of this paper, will probably help us find in-spiration for this.

4. Conclusions and outlook: And what about your library?

As one of several new roles for academic librarians, Ronald C. Jantz defines the “marketing librarian” as somebody who “matches client needs with the services and resources of the library”.84 In doing so, this role provides an important bridge between ongoing library research that generates new knowledge and ideas and the evolving needs of students and faculty. Jantz thinks that “the marketing librarian constitutes a new role, one whose duties differ from the marketing and outreach conducted by the library liaison” because he or she “spans all the scholarly disciplines and spends much of his or her time outside the library, communicating with faculty, students, and administrators”, as “one of the more important functions in the marketing role might be understanding how stakeholders think”. While Jantz aims at legislators, provosts, and administrators as the main stakeholders here, the same role should be expected, e.g., from liaison librarians with students and faculty as their primary stakeholders: Every (subject or liaison) librarian can become a subject marketing librarian!

Karen Munro adopted the “seven touches” or “rule of seven” marketing model for an outreach project.85 This model assumes that “it takes seven ‘touches’ for a potential customer to accept your call to action”86, following the theory of the “mere-exposure effect”. As Munro and her small team cannot personally reach out to every user of their library seven times, they “decided to use at least seven methods of promoting [a] survey, with the expectation that some users would encounter the promotion multiple times”.87 As with many marketing activities, they could not directly attribute the high number of responses to their survey to these seven types of activities, but their “anecdotal experience is that [their] efforts were at least partly to thank for the increase”.88 So when you think about promoting your collections try to find more than one way of reaching out to your different stakeholders, following a “multi-pronged” strategy like Munro and her team. The examples from our survey can hopefully give you some inspiration for this.

For further research, it might be interesting to enlarge this collection with examples from other academic and research libraries (e.g. the LIBER members89) and also take into account public libraries, which are often more active in “all things marketing”, to broaden the scope.90 Moreover, we should also include the viewpoint of library users: An investigation asking whether they may have informational needs regarding collections that are not yet met by libraries would be an interesting complement to our study. Besides this, combining the “seven touches” model with user experience or attention span studies may give interesting results to further develop marketing ideas.91

Another paper could investigate the validity and productivity of different marketing approaches, thus evaluating the possible applicability of our findings for various library settings such as academic, public, or special libraries. Such a paper could also address questions and theories on cultural differences in library marketing. It might also be valuable to investigate in what manner our limited, although global, survey positions itself in respect to other large global library communities: As we are rooted in Western/European libraries, we may miss aspects of what constitutes productive collection marketing in other parts of the world.

Meanwhile, we would like to encourage you to think about and start marketing your collections in ways that you think are inspiring and productive – your collections surely deserve it!

References

- Armstrong, Alison M.; Dinkle, Lisa: The library liaisonʼs training guide to collection management. Chicago 2020.

- Arthur, Michael A.: Being Earnest with Collections. Building a Successful Marketing Program at The University of Alabama, in: Against the Grain 29 (3), 2017, pp. 75–77. Online: <http://dx.doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.7810>.

- Arthur, Michael A.: Developing a Collections Marketing Program at the University of Alabama. Presentation at the ALA Annual 2018: Technical Services Managers in Academic Libraries Interest Group, 23.6.2018. Online: <http://ir.ua.edu/handle/123456789/3713>.

- Crawford, Scott; Syme, Fiona: Enhancing Collection Development with Big Data Analytics, in: Public Library Quarterly 37 (4), 2018, p. 387–393. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2018.1514922>.

- Dudenhoffer, Cynthia: Pin it! Pinterest as a library marketing and information literacy tool, in: College & Research Libraries News 73 (6), 2012, pp. 328–332. Online: <https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.73.6.8775>.

- Eden, Bradford Lee: Marketing and outreach for the academic library. New approaches and initiatives, Lanham 2016.

- Fought, Rick L.; Gahn, Paul; Mills, Yvonne: Promoting the Library Through the Collection Development Policy. A Case Study, in: Journal of Electronic Resources in Medical Libraries 11 (4), 2014, pp. 169–178. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/15424065.2014.969031>.

- Georgy, Ursula; Schade, Frauke (ed.): Praxishandbuch Informationsmarketing. Konvergente Strategien, Methoden und Konzepte, Berlin; Boston 2018. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110539011>.

- Hermes, Jürgen: Chirpy Humanities, Public Humanities, 05.07.2021, <https://publicdh.hypo theses.org/42>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

- Hicks, Sarah; White, Kristy; Behary, Rob: The Correlation of LibGuides to Print and Electronic Book Usage. A Method for Assessing LibGuide Usage, in: Journal of Web Librarianship 15 (1), 2021, pp. 1–17. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2021.1884927>.

- Hursh, Angela: Beginner’s Guide to Promoting Your Collection. How to Get Started and Drive Circulation at Your Library, Super Library Marketing: Practical Tips and Ideas for Library Promotion, 25.10.2021, <https://superlibrarymarketing.com/2021/10/25/beginnercollection promotion>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

- Jackson, Jennifer: Making the Most of Library Collections, While Multitasking: A Review of Best Practices for Marketing and Promoting Library Collections, in: Against the Grain 28 (4), 2016, pp. 38–40. Online: <https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.7458>.

- Jantz, Ronald C.: A vision for the future. New roles for academic librarians, in: Gilman, Todd (ed.): Academic librarianship today, Washington, DC 2017, pp. 223–235

- Kennedy, Marie R.; LaGuardia, Cheryl: Marketing your libraryʼs electronic resources. A how-to-do-it manual, Chicago 20182.

- McPhie, Joanne; Wannerton, Rob: Marketing our collections, in: SCONUL Focus 61, 2014, pp. 39–41. Online: <https://www.sconul.ac.uk/page/focus-61>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

- Munro, Karen: At Least Seven Touches. One Academic Library’s Marketing and Outreach Strategy for Graduate Professional Programs. in: Public Services Quarterly 13 (3), 2017, pp. 200–206. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2017.1328297>.

- Patel, Jashvant: Marketing Library Resources, Products and Services in University Library: A Case Study of Uka Tarsadia University, in: International Conference on Sustainable Librarianship: Reimagining and Reengineering Libraries, Baroda Gujarat India, 19–21 December 2019. Online: <http://eprints.rclis.org/40937/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

- Perrin, Joy M.; Winkler, Heidi; Daniel, Kaley; Barba, Shelley; Yang, Le: Know Your Crowd: A Case Study in Digital Collection Marketing, in: The Reference Librarian, 58 (3), 2017, pp. 190–201. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2016.1271758>.

- Polger, Mark Aaron: Library marketing basics, Lanham 2019.

- Potter, Ned: The library marketing toolkit, London 2012.

- Potter, Ned: Marketing Libraries Is like Marketing Mayonnaise, Library Journal, 18.04.2013. Online: <http://www.libraryjournal.com/?detailStory=marketing-libraries-is-like-marketing-mayonnaise>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

- Thomsett-Scott, Beth C: Marketing with social media. A LITA guide, Chicago 2014.

- Vaaler, Alyson: Brantley, Steve: Using a blog and social media promotion as a collaborative community building marketing tool for library resources, in: Library Hi Tech News 33 (5), 2016, pp. 13–15. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-04-2016-0017>.

- Waller, Liz; Burg, Judy: Durham Residential Research Library. Presentation at the 48th LIBER Annual Conference Dublin 2019, 27.6.2019. Online: <https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3258200>.

- Westbrook, R. Niccole; Prilop, Valerie; German, Elizabeth M.: Nerd thrill your users: Collaborating with liaisons to create an appealing gateway to digital collections, in: Reference Services Review, 40 (3), 2012, pp. 469–479. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321211254706>.

- Wissel, Kathryn M.; DeLuca, Lisa: Telling the Story of a Collection with Visualizations: A Case Study, in: Collection Management 43 (4), 2018, pp. 265–275. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2018.1524319>.

1 Cf. Crawford, Scott; Syme, Fiona: Enhancing Collection Development with Big Data Analytics, in: Public Library Quarterly 37 (4), 2018, p. 387–393. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2018.1514922>.

2 See e.g. Patel, Jashvant: Marketing Library Resources, Products and Services in University Library: A Case Study of Uka Tarsadia University, in: International Conference on Sustainable Librarianship: Reimagining and Reengineering Libraries, Baroda Gujarat India, 19–21 December 2019. Online: <http://eprints.rclis.org/40937/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

3 A shorter version of this paper was presented at the 41th Annual IATUL Conference 2021. The slides, the talk notes, and a recording of the talk can be found at <https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hbz:6-16079547855>, last accessed 09.04.2022. A recording of the conference session can be found on IATUL’s YouTube channel at <https://youtu.be/JIM6Eq_snMc>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

4 The hashtag “#AACOAbooks” for “Anglo-American Culture Open Access Books”, started in March 2021 by the Library of Anglo-American Culture & History at the State and University Library Göttingen, Germany, can serve as an example for this: <https://twitter.com/hashtag/AACOAbooks?f=live>.

5 IATUL: International Association of University Libraries, <https://iatul.org>, last accessed 09.04.2022. Thanks to the IATUL office for providing us with a list of the member libraries as of February 2021. The links to their websites were collected via the IATUL website, <https://www.iatul.org/members>.

6 An example for this is the National Institute of Library & Information Sciences of the University of Colombo: The institute’s library’s website is available at <https://nilis.cmb.ac.lk/home/nilis-library/>, the parent university library at <https://lib.cmb.ac.lk>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

7 Cf. SpringShare: LibGuides, <https://www.springshare.com/libguides/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

8 CERN library catalogue, <https://catalogue.library.cern/search?q=&f=doctype%3ABOOK&f=medium%3AE-BOOK&l=grid&order=desc&p=1&s=15&sort=created>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

9 Tshwane University of Technology Library: Library and Information Services, <https://tkplib01.tut.ac.za/ftlist/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

10 Universität Konstanz: Neuerwerbungen nach Gruppen, <https://katalog.uni-konstanz.de/libero/WebOpac.cls?VERSION=2&ACTION=NEWITEMSGROUP&RSN=&DATA=KON&TOKEN=rsE51pG5fd2413&Z=1&NewBreadCrumb=1>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

11 Universität Innsbruck: Unsere neuen Bücher, <https://www.uibk.ac.at/ulb/ressourcen/neuzugaenge/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

12 Free University of Bozen-Bolzano: New Books, <https://www.unibz.it/en/services/library/new-books/#report===new-print-books>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

13 Massey University: New Titles available at Massey University, <https://www.massey.ac.nz/~wwwlib/find-information/new-titles_home.php>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

14 Sabancı University: Alert Service, <https://www.sabanciuniv.edu/bm/en/research-guide/alerting-services>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

15 University of Adelaide, University Library: 2020 Arrivals and Departures, <https://www.adelaide.edu.au/library/collections/arrivals-departures/2020-arrivals-and-departures>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

16 MacEwan University, Library: Library News, <https://library.macewan.ca/about/library-news/article/1611>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

17 University of Otago Library: Library services and resources to support your learning, research and teaching needs, <https://www.otago.ac.nz/library/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

18 Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Library, <https://library.ust.hk/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

19 Università Bocconi, <https://lib.unibocconi.it/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

20 Islamic University of Technology, Library: <http://library.iutoic-dhaka.edu/main/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

21 Curtin University Library: Virtual Bookshelf, <https://bookshelf.library.curtin.edu.au/newbooks>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

22 American University of Sharjah, University Library: New Book Feeds, <https://library.aus.edu/newbooks>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

23 Technical University of Chemnitz, University Library: Catalogue, <https://katalog.bibliothek.tu-chemnitz.de>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

24 University of Porto library: UP Catalogue, <https://catalogo.up.pt/F/?con_lng=eng>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

25 Beirut Arab University Library: Library catalog, <http://librarycatalog.bau.edu.lb/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

26 Macquarie University Library: Collections, <https://www.mq.edu.au/about/campus-services-and-facilities/library/collections>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

27 Hildesheim University Library: Neuerwerbungen, <https://www.uni-hildesheim.de/bibliothek/suchen-finden/

neuerwerbungen/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

28 Beirut Arab University Library: Current Awareness, <https://www.bau.edu.lb/Libraries/Current-Awareness>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

29 University of Melbourne library: Staying Current: keeping up-to-date, <https://unimelb.libguides.com/c.php?

g=936537&p=6773225>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

30 University of Turku, Library: Education, <https://utuguides.fi/education/newbooks>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

31 Atilim University, Kadriye Zaim Library: Engineering: Books & eBooks, <https://atilim.libguides.com/Engineering/BooksandeBooks>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

32 University of Western Cape: New Books List, <https://libguides.uwc.ac.za/newbookslist>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

33 Deakin University Library: Trial databases and new electronic resources, <https://deakin.libguides.com/trials_new>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

34 University of Melbourne: Library Guides, <https://library.unimelb.edu.au/library-guides>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

35 McMaster University Library: Maud’s e-Resource of the Week, e.g., <https://twitter.com/maclibraries/status/

1395357230497730562>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

36 Indian Institute of Technology: Book of the week, e.g., <https://twitter.com/LibraryIITGN/

status/1407639570523594754>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

37 Belarusian National Technical University Library, e.g., <https://twitter.com/biblioteka/status/1388153138465677320>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

38 Kingdom University Library: Information on WhatsApp group for new media, <https://www.ku.edu.bh/library/>, last accessed 09.04.2022. (Choose the box „Services“ and scroll down to reach the “New Arrivals Titles announcement” section.)

39 Cf. Dudenhoffer, Cynthia: Pin it! Pinterest as a library marketing and information literacy tool, in : College & Research Libraries News 73 (6), 2012, pp. 328–332. Online: <https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.73.6.8775>. The Pinterest board can be found at <https://www.pinterest.de/cmu_library/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

40 Overview over all lists: <https://www.sub.uni-goettingen.de/sub-a-z/schlagwort/tags/neuerwerbungen/>; example for one subject: <https://www.sub.uni-goettingen.de/geisteswissenschaften-und-theologie/anglistik-amerikanistik/neuerwerbungen/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

41 Groningen University Library, e.g., <https://twitter.com/Bibliothecaris/status/1457709591039467521>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

42 Hagen University Library: Neuerwerbungen der Universitätsbibliothek Hagen, <http://www.ub.fernuni-hagen.de/neuerwerbungen/>, last accessed 09.04.2022. Cf. also this mention on Twitter: <https://twitter.com/ubhagen/

status/1445728043968962560>.

43 DESY stands for „Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron“, in English „German Electron Synchrotron research centre“.

44 DESY Central Library: New articles and books this week, <https://library.desy.de/our_collection/new_articles_books/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

45 KU Leuven libraries, Artes University Library, <https://bib.kuleuven.be/english/artes/ub> and New acquisitions, <https://bib.kuleuven.be/english/artes/acquiartes>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

46 Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, e.g., <https://twitter.com/FID_Ost/status/1407597880995684354>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

47 A screenshot can be seen at <https://twitter.com/v_i_o_l_a/status/1220751435547250688>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

48 The box is on the library’s homepage <https://www.lib.berkeley.edu/> in the spring/summer months; the blog post category is <https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/tag/summer-reading-list/>.

49 Cf. Vaaler, Alyson; Brantley, Steve: Using a blog and social media promotion as a collaborative community building marketing tool for library resources, in: Library Hi Tech News 33 (5), 2016, pp. 13–15. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-04-2016-0017>, and EIU Booth Library: Library news, <https://library.eiu.edu/refnews/>, last accessed 09.04.2022. By now posts of this kind also exist in other blog categories, <https://castle.eiu.edu/boothnews/>.

50 Cf. Jackson, Jennifer: Making the Most of Library Collections, While Multitasking: A Review of Best Practices for Marketing and Promoting Library Collections, in: Against the Grain 28 (4), 2016, pp. 38–40. Online: <https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.7458>, p. 38. Other libraries have taken up the hashtag as well. For examples, see <https://twitter.com/hashtag/BooksYouDidntKnowWeHad?src=hashtag_click>.

51 Hochschule Hannover: Biblioblog, Zeitschriften-Tipp des Monats, <https://blog.bib.hs-hannover.de/tag/zeitschriften-tipp-des-monats/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

52 Cf. McPhie, Joanne; Wannerton, Rob: Marketing our collections, in: SCONUL Focus 61, 2014, pp. 39–41. Online: <https://www.sconul.ac.uk/page/focus-61>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

53 Tübingen University Library: Books To Go, <https://uni-tuebingen.de/einrichtungen/universitaetsbibliothek/ueber-uns/veranstaltungen-ausstellungen/books-to-go/#c1212919>, last accessed 09.04.2022. Example for a blog post: <https://uni-tuebingen.de/einrichtungen/universitaetsbibliothek/home/newsfullview-home/article/ukraine-books-to-go/>.

54 Vienna University Library: FB Judaistik – E-Books des Monats, <https://bibliothek.univie.ac.at/fb-judaistik/fb_judaistik_e-books_des_monats_.html>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

55 Example for this hashtag by the University Library Bochum: <https://twitter.com/hashtag/Datenbankdienstag>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

56 Zentralbibliothek Zürich, e.g., <https://twitter.com/ZBZuerich/status/1414842029901713441>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

57 Cf. Waller, Liz; Burg, Judy: Durham Residential Research Library. Presentation at the 48th LIBER Annual Conference Dublin 2019, 27.6.2019. Online: <https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3258200>. This program only needs some “internal and philanthropic funding” …

58 Cf. Westbrook, R. Niccole; Prilop, Valerie; German, Elizabeth M.: Nerd thrill your users: Collaborating with liaisons to create an appealing gateway to digital collections, in: Reference Services Review, 40 (3), 2012, pp. 469–479. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321211254706>. The Image Café seems to have gone offline by now. But the idea of “nerd thrill” could still work for some collections – or some users – today, 10 years on.

59 Cf. Perrin, Joy M.; Winkler, Heidi; Daniel, Kaley; Barba, Shelley; Yang, Le: Know Your Crowd: A Case Study in Digital Collection Marketing, in: The Reference Librarian, 58 (3), 2017, pp. 190–201. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2016.1271758>.

60 Cf. Wissel, Kathryn M.; DeLuca, Lisa: Telling the Story of a Collection with Visualizations: A Case Study, in: Collection Management 43 (4), 2018, pp. 265–275. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2018.1524319>, and Valente Italian Library: Visualizations: <https://web.archive.org/web/20210512175909/https://library.shu.edu/valente/

visualizations>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

61 Cf. Arthur, Michael A.: Being Earnest with Collections. Building a Successful Marketing Program at The University of Alabama, in: Against the Grain 29 (3), 2017, pp. 75–77. Online: <http://dx.doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.7810>, and Arthur, Michael A.: Developing a Collections Marketing Program at the University of Alabama. Presentation at the ALA Annual 2018: Technical Services Managers in Academic Libraries Interest Group, 23.6.2018. Online: <http://ir.ua.edu/handle/123456789/3713>. The lessons learned and the key aspects of the librarys’ marketing program presented in Arthur: Being Earnest with Collections, 2017, as well as the discussion questions on pp. 12–13 in Arthur: Developing a Collections Marketing Program, 2018, might be helpful for developing such programs in other libraries. Cf. also Jackson: Making the Most of Library Collections, for some aspects of starting marketing activities.

62 Armstrong, Alison M.; Dinkle, Lisa: The library liaisonʼs training guide to collection management. Chicago 2020, p. 43.

63 Cf. Hermes, Jürgen: Chirpy Humanities, Public Humanities, 05.07.2021, <https://publicdh.hypotheses.org/42>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

64 Cf., e.g., the articles in the volume edited by Georgy, Ursula; Schade, Frauke (ed.): Praxishandbuch Informationsmarketing. Konvergente Strategien, Methoden und Konzepte, Berlin; Boston 2018. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110539011>; Polger, Mark Aaron: Library marketing basics, Lanham 2019; Kennedy, Marie R.; LaGuardia, Cheryl: Marketing your libraryʼs electronic resources. A how-to-do-it manual, Chicago 20182; Eden, Bradford Lee: Marketing and outreach for the academic library. New approaches and initiatives, Lanham 2016; Thomsett-Scott, Beth C: Marketing with social media. A LITA guide, Chicago 2014; or Potter, Ned: The library marketing toolkit, London 2012, as some examples from the last 10 years.

65 Münster University Library: Neuerwerbungslisten, <https://www.ulb.uni-muenster.de/ULB/neuerwerbungslisten/>, last accessed 09.04.2022 (only available in German).

66 Example at <https://www.ulb.uni-muenster.de/bibliothek/aktuell/nachricht/2724>, last accessed 09.04.2022 (only available in German).

67 Münster University Library: Recherche, <https://www.ulb.uni-muenster.de/recherche/fach/>, last accessed 09.04.2022 (choose “Sprache, Literatur und Kultur”, only available in German).

68 Münster University Library, Medical Library: Aktuelles, <https://www.uni-muenster.de/ZBMed/aktuelles/>, last accessed 09.04.2022 (posts written in German, translation in different languages via automatic translation).

69 Münster University Library: FachBlog, <https://www.ulb.uni-muenster.de/fachblog/>, last accessed 09.04.2022. Its name, “FachBlog”, derives from the German word “Fach” for ‘subject’.

70 Example at <https://www.ulb.uni-muenster.de/recherche/fach/lit/aktuell.html>, last accessed 09.04.2022. The different feeds are aggregated via FeedInformer, <http://feed.informer.com>.

71 MSUL Subject Services Twitter account, <https://twitter.com/ULB_MS_FachInfo>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

72 IFFTTT, <https://ifttt.com>, last accessed 09.04.2022. A follow-up project to this was the start of a Twitter account for promoting historical documents digitised by MSUL in January 2021: <https://twitter.com/ULB_MS_DigiNews>, last accessed 09.04.2022. New documents are sent to the account via RSS and IFTTT.

73 Examples: <https://twitter.com/ULB_MS_FachInfo/status/1394534485996212227> for a new acquisition, <https://twitter.com/ULB_MS_FachInfo/status/1402238276551970819> for a talk organized by an institute of Münster University, <https://twitter.com/ULB_MS_FachInfo/status/1403249193427296257> for a recommendation of a new weblog, or <https://twitter.com/ULB_MS_FachInfo/status/1402236519595839490> for mentioning a new research tool, all last accessed 09.04.2022.

74 Tweet at <https://twitter.com/ULB_MS_FachInfo/status/1482974134103588866>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

75 Münster University Library: Neuerwerbungen, Links und Tipps für die Anglistik aus der ULB, <https://www.ulb.uni-muenster.de/recherche/fach/ang/aktuell.html>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

76 These subjects are: Asian & African Studies, English Studies, German Studies, Nordic/Scandinavian Studies, Romance Studies, Slavic Studies, General Linguistics and Literature Studies, and Digital Humanities.

77 Blog posts in the category „Neuerwerbungen“, <https://www.ulb.uni-muenster.de/fachblog/archiv/category/

neuerwerbungen>.

78 Hicks, Sarah; White, Kristy; Behary, Rob: The Correlation of LibGuides to Print and Electronic Book Usage. A Method for Assessing LibGuide Usage, in: Journal of Web Librarianship 15 (1), 2021, pp. 1–17. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2021.1884927>.

79 Thanks to Britta Colver, MSUL, for collecting the usage data and for carrying out the statistical analysis!

80 Fought, Rick L.; Gahn, Paul; Mills, Yvonne: Promoting the Library Through the Collection Development Policy. A Case Study, in: Journal of Electronic Resources in Medical Libraries 11 (4), 2014, pp. 169–178. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/15424065.2014.969031>, p. 176.

81 Blog posts in the category „wissen.leben.lesen“, <https://go.wwu.de/wissenlebenlesen>.

82 Armstrong; Dinkle, The library liaison’s training guide to collection management, p. 46: “Sending a special book to a newly tenured faculty member: Every year, when newly tenured faculty members are announced, the appropriate liaison sends a congratulatory email to the faculty member asking them to choose a book, either on our collection or one we purchase, which will be bookplated in their honor. We also ask them to share the reason they chose this book. It is a small gesture from the library to recognize their achievement, but it is appreciated.” Bookplated books are rather rare in German university libraries, and what to do with ebooks? Hence the idea of a blog post series came up.

83 Münster University Library: Projekt Go:Al, <https://www.ulb.uni-muenster.de/bibliothek/aktivitaeten/projekte/alma.html>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

84 Jantz, Ronald C.: A vision for the future. New roles for academic librarians, in: Gilman, Todd (ed.): Academic librarianship today, Washington, DC 2017, pp. 223–235, here p. 226.

85 Cf. Munro, Karen: At Least Seven Touches. One Academic Library’s Marketing and Outreach Strategy for Graduate Professional Programs. in: Public Services Quarterly 13 (3), 2017, pp. 200–206. Online: <https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2017.1328297>.

86 Ibid., p. 201.

87 Ibid., pp. 204–205. They used the libraryʼs Facebook page, their students’ own Facebook group, the quarterly library e-newsletter for one of the faculties, the staff and faculty discussion list. Besides that they designed a card that they distributed as a postcard inserted into books the students checked out or as a table-topper in the library’s public space as well as in departmental and shared instructional spaces like the libraryʼs computer classroom or on their mobile “pop-up” library service cart when visiting the departments. Finally “library staff reminded students, staff, and faculty about the survey in person on multiple occasions”.

88 Ibid., p. 205. Cf. also e.g. Potter, Ned: Marketing Libraries Is like Marketing Mayonnaise, Library Journal, 18.04.2013. Online: <http://www.libraryjournal.com/?detailStory=marketing-libraries-is-like-marketing-mayonnaise>, last accessed 09.04.2022: “One-off promotions expect too much of our users and potential users. It’s more important (and more realistic) to build up awareness of the services we offer to relevant groups over a period of time, so that when they DO require something we provide, we’re the first thing they think of.”

89 LIBER: LIBER participants, <https://libereurope.eu/liber-participants/>, last accessed 09.04.2022.

90 Cf. Hursh, Angela: Beginner’s Guide to Promoting Your Collection. How to Get Started and Drive Circulation at Your Library, Super Library Marketing: Practical Tips and Ideas for Library Promotion, 25.10.2021, <https://superlibrary marketing.com/2021/10/25/beginnercollectionpromotion>, last accessed 09.04.2022, who noticed this: “I was at the Association of Rural and Small Libraries Conference last week […]. I asked the group where their library spends most of its promotional resources. 75 % said promoting programs and events. A mere FOUR PERCENT said promoting their collection.”

91 Thanks to Antje Gildhorn, MSUL, for bringing up this idea.

Fig. 5: Massey University Library: New Titles available page

Fig. 5: Massey University Library: New Titles available page